| Learn how to create and use a logic model, a visual representation of your initiative's activities, outputs, and expected outcomes. |

-

What is a logic model?

-

When can a logic model be used?

-

How do you create a logic model?

-

What makes a logic model effective?

-

What are the benefits and limitations of logic modeling?

What is a logic model?

A logic model presents a picture of how your effort or initiative is supposed to work. It explains why your strategy is a good solution to the problem at hand. Effective logic models make an explicit, often visual, statement of the activities that will bring about change and the results you expect to see for the community and its people. A logic model keeps participants in the effort moving in the same direction by providing a common language and point of reference.

More than an observer's tool, logic models become part of the work itself. They energize and rally support for an initiative by declaring precisely what you're trying to accomplish and how.

In this section, the term logic model is used as a generic label for the many ways of displaying how change unfolds.

Some other names include:

- road map, conceptual map, or pathways map

- mental model

- blueprint for change

- framework for action or program framework

- program theory or program hypothesis

- theoretical underpinning or rationale

- causal chain or chain of causation

- theory of change or model of change

Each mapping or modeling technique uses a slightly different approach, but they all rest on a foundation of logic - specifically, the logic of how change happens. By whatever name you call it, a logic model supports the work of health promotion and community development by charting the course of community transformation as it evolves.

A word about logic

The word "logic" has many definitions. As a branch of philosophy, scholars devote entire careers to its practice. As a structured method of reasoning, mathematicians depend on it for proofs. In the world of machines, the only language a computer understands is the logic of its programmer.

There is, however, another meaning that lies closer to heart of community change: the logic of how things work. Consider, for example, the logic to the motion of rush-hour traffic. No one plans it. No one controls it. Yet, through experience and awareness of recurrent patterns, we comprehend it, and, in many cases, can successfully avoid its problems (by carpooling, taking alternative routes, etc.).

Logic in this sense refers to "the relationship between elements and between an element and the whole." All of us have a great capacity to see patterns in complex phenomena. We see systems at work and find within them an inner logic, a set of rules or relationships that govern behavior. Working alone, we can usually discern the logic of a simple system. And by working in teams, persistently over time if necessary, there is hardly any system past or present whose logic we can't decipher.

On the flip side, we can also project logic into the future. With an understanding of context and knowledge about cause and effect, we can construct logical theories of change, hypotheses about how things will unfold either on their own or under the influence of planned interventions. Like all predictions, these hypotheses are only as good as their underlying logic. Magical assumptions, poor reasoning, and fuzzy thinking increase the chances that despite our efforts, the future will turn out differently than we expect or hope. On the other hand, some events that seem unexpected to the uninitiated will not be a surprise to long-time residents and careful observers.

The challenge for a logic modeler is to find and accurately represent the wisdom of those who know best how community change happens.

The logic in logic modeling

Like a road map, a logic model shows the route traveled (or steps taken) to reach a certain destination. A detailed model indicates precisely how each activity will lead to desired changes. Alternatively, a broader plan sketches out the chosen routes and how far you will go. This road map aspect of a logic model reveals what causes what, and in what order. At various points on the map, you may need to stop and review your progress and make any necessary adjustments.

A logic model also expresses the thinking behind an initiative's plan. It explains why the program ought to work, why it can succeed where other attempts have failed. This is the "program theory" or "rationale" aspect of a logic model. By defining the problem or opportunity and showing how intervention activities will respond to it, a logic model makes the program planners' assumptions explicit.

The form that a logic model takes is flexible and does not have to be linear (unless your program's logic is itself linear). Flow charts, maps, or tables are the most common formats. It is also possible to use a network, concept map, or web to describe the relationships among more complex program components. Models can even be built around cultural symbols that describe transformation, such as the Native American medicine wheel, if the stakeholders feel it is appropriate.

See the "Generic Model for Disease/Injury Control and Prevention" in the Examples section for an illustration of how the same information can be presented in a linear or nonlinear format.

Whatever form you choose, a logic model ought to provide direction and clarity by presenting the big picture of change along with certain important details. Let's illustrate the typical components of a logic model, using as an example a mentoring program in a community where the high-school dropout rate is very high. We'll call this program "On Track."

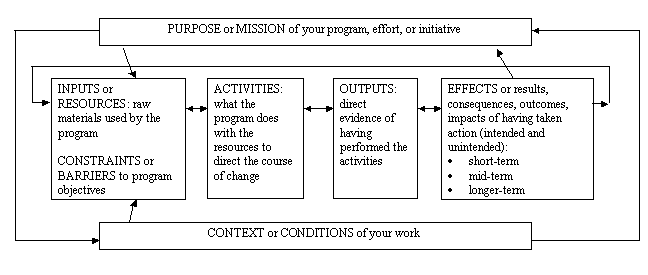

- Purpose, or mission. What motivates the need for change? This can also be expressed as the problems or opportunities that the program is addressing. (For On Track, the community focused advocates on the mission of enhancing healthy youth development to improve the high-school dropout rate.)

- Context, or conditions. What is the climate in which change will take place? (How will new policies and programs for On Track be aligned with existing ones? What trends compete with the effort to engage youth in positive activities? What is the political and economic climate for investing in youth development?)

- Inputs, or resources or infrastructure. What raw materials will be used to conduct the effort or initiative? (In On Track, these materials are coordinator and volunteers in the mentoring program, agreements with participating school districts, and the endorsement of parent groups and community agencies.) Inputs can also include constraints on the program, such as regulations or funding gaps, which are barriers to your objectives.

- Activities, or interventions. What will the initiative do with its resources to direct the course of change? (In our example, the program will train volunteer mentors and refer young people who might benefit from a mentor.) Your intervention, and thus your logic model, should be guided by a clear analysis of risk and protective factors.

- Outputs. What evidence is there that the activities were performed as planned? (Indicators might include the number of mentors trained and youth referred, and the frequency, type, duration, and intensity of mentoring contacts.)

- Effects, or results, consequences, outcomes, or impacts. What kinds of changes came about as a direct or indirect effect of the activities? (Two examples are bonding between adult mentors and youth and increased self-esteem among youth.)

Putting these elements together graphically gives the following basic structure for a logic model. The arrows between the boxes indicate that review and adjustment are an ongoing process - both in enacting the initiative and developing the model.

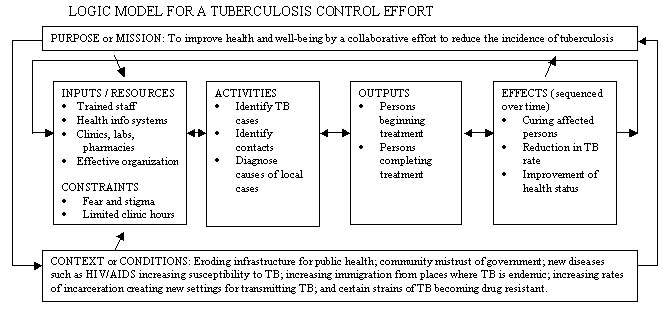

Using this generic model as a template, let's fill in the details with another example of a logic model, one that describes a community health effort to prevent tuberculosis.

Remember, although this example uses boxes and arrows, you and your partners in change can use any format or imagery that communicates more effectively with your stakeholders.

As mentioned earlier, the generic model for Disease/Injury Control and Prevention in Examples depicts the same relationship of activities and effects in a linear and a nonlinear format. The two formats helped communicate with different groups of stakeholders and made different points.

The linear model better guided discussions of cause and effect and how far down the chain of effects a particular program was successful. The circular model more effectively depicted the interdependence of the components to produce the intended effects.

When exploring the results of an intervention, remember that there can be long delays between actions and their effects. Also, certain system changes can trigger feedback loops, which further complicate and delay our ability to see all the effects. (A definition from the System Dynamics Society, might help here: "Feedback refers to the situation of X affecting Y and Y in turn affecting X perhaps through a chain of causes and effects. One cannot study the link between X and Y and, independently, the link between Y and X and predict how the system will behave. Only the study of the whole system as a feedback system will lead to correct results.")

For these reasons, logic models indicate when to expect certain changes. Many planners like to use the following three categories of effects (illustrated in the models above), although you may choose to have more or fewer depending on your situation.

- Short-term or immediate effects. (In the On Track example, this would be that young people who participate in mentoring improve their self-confidence and understand the importance of staying in school.)

- Mid-term or intermediate effects. (Mentored students improve their grades and remain in school.)

- Longer-term or ultimate effects. (High school graduation rates rise, thus giving graduates more employment opportunities, greater financial stability, and improved health status.)

Here are two important notes about constructing and refining logic models.

Outcome or Impact?

Clarify your language. In a collaborative project, it is wise to anticipate confusion over language. If you understand the basic elements of a logic model, any labels can be meaningful provided stakeholders agree to them. In the generic and TB models above, we called the effects short-, mid-, and long-term. It is also common to hear people talk about effects that are "upstream" or "proximal" (near to the activities) versus "downstream" or "distal" (distant from the activities). Because disciplines have their own jargon, stakeholders from two different fields might define the same word in different ways.

Some people are trained to call the earliest effects "outcomes" and the later ones "impacts." Other people are taught the reverse: "impacts" come first, followed by "outcomes." The idea of sequence is the same regardless of which terms you and your partners use. The main point is to clearly show connections between activities and effects over time, thus making explicit your initiative's assumptions about what kinds of change to expect and when. Try to define essential concepts at the design stage and then be consistent in your use of terms. The process of developing a logic model supports this important dialogue and will bring potential misunderstandings into the open.

For good or for ill?

Understand effects. While the starting point for logic modeling is to identify the effects that correspond to stated goals, your intended effect are not the only effects to watch for. Any intervention capable of changing problem behaviors or altering conditions in communities can also generate unintended effects. These are changes that no one plans and that might somehow make the problem worse.

Many times our efforts to solve a problem lead to surprising, counterintuitive results. There is always a risk that our "cure" could be worse than the "disease" if we're not careful. Part of the added value of logic modeling is that the process creates a forum for scrutinizing big leaps of faith, a way to searching for unintended effects. (See the discussion of simulation in "What makes a logic model effective" for some thoughts on how to do this in a disciplined manner.)

One of the greatest rewards for the extra effort is the ability to spot potential problems and redesign an initiative (and its logic model) before the unintended effects get out of hand, so that the model truly depicts activities that will plausibly produce the intended effects.

Choosing the right level of detail: the importance of utility and simplicity

It may help at this point to consider what a logic model is not. Although it captures the big picture, it is not an exact representation of everything that's going on. All models simplify reality; if they didn't, they wouldn't be of much use.

Even though it leaves out information, a good model represents those aspects of an initiative that, in the view of your stakeholders, are most important for understanding how the effort works. In most cases, the developers will go through several drafts before producing at a version that the stakeholders agree accurately reflects their story.

Should the information become overly complex, it is possible to create a family of related models, or nested models, each capturing a different level of detail. One model could sketch out the broad pathways of change, whereas others could elaborate on separate components, revealing detailed information about how the program operates on a deeper level. Individually, each model conveys only essential information, and together they provide a more complete overview of how the program or initiative functions. (See "How do you create a logic model?" for further details.)

Imagine "zooming-in" on the inner workings of a specific component and creating another, more detailed model just for that part. For a complex initiative, you may choose to develop an entire family of such related models that display how each part of the effort works, as well as how all the parts fit together. In the end, you may have some or all of the following family of models, each one differing in scope:

- View from Outer Space. This overall road map shows the major pathways of change and the full spectrum of effects. This view answers questions such s: Do the activities follow a single pathway, or are there separate pathways that converge down the line? How far does the chain of effects go? How do our program activities align with those of other organizations? What other forces might influence the effects that we hope to see? Where can we anticipate feedback loops and in what direction will they travel? Are there significant time delays between any of the connections?

- View from the Mountaintop. This closer view focuses on a specific component or set of components, yet it is still broad enough to describe the infrastructure, activities, and full sequence of effects. This view answers the same questions as the view from outer space, but with respect to just the selected component(s).

- You Are Here. This view expands on a particular part of the sequence, such as the roles of different stakeholders, staff, or agencies in a coalition, and functions like a flow chart for someone's work plan. It is a specific model that outlines routine processes and anticipated effects. This is the view that you might need to understand quality control within the initiative.

Families, Nesting, and Zooming-In

In the Examples section, the idea of nested models is illustrated in the Tobacco Control family of models. It includes a global model that encompasses three intermediate outcomes in tobacco control - environments without tobacco smoke, reduced smoking initiation among youth, and increased cessation among youth and adults. Then a zoom-in model is elaborated for each one of these intermediate outcomes.The Comprehensive Cancer model illustrates a generic logic model accompanied by a zoom-in on the activities to give program staff the specific details they need. Notably, the intended effects on the zoom-in are identical to those on the global model and all major categories of activities are also apparent. But the zoom in unpacks these activities into their detailed components and, more important, indicates that the activities achieve their effects by influencing intermediaries who then move gatekeepers to take action. This level of detail is necessary for program staff, but it may be too much for discussions with funders and stakeholders.

The Diabetes Control model is another good example of a family of models. In this case, the zoom in models are very similar to the global model in level of detail. They add value by translating the global model into a plan for specific actors (in this case a state diabetes control program) or for specific objectives (e..g., increasing timely foot exams).

When can a logic model be used?

Logic models are useful for both new and existing programs and initiatives. If your effort is being planned, a logic model can help get it off to a good start. Alternatively, if your program is already under way, a model can help you describe, modify or enhance it.

Planners, program managers, trainers, evaluators, advocates and other stakeholders can use a logic model in several ways throughout an initiative. One model may serve more than one purpose, or it may be necessary to create different versions tailored for different aims. Here are examples of the various times that a logic model could be used.

During planning to:

- clarify program strategy

- identify appropriate outcome targets (and avoid over-promising)

- align your efforts with those of other organizations

- write a grant proposal or a request for proposals

- assess the potential effectiveness of an approach

- set priorities for allocating resources

- estimate timelines

- identify necessary partnerships

- negotiate roles and responsibilities

- focus discussions and make planning time more efficient

During implementation to:

- provide an inventory of what you have and what you need to operate the program or initiative

- develop a management plan

- incorporate findings from research and demonstration projects

- make mid-course adjustments

- reduce or avoid unintended effects

During staff and stakeholder orientation to:

- explain how the overall program works

- show how different people can work together

- define what each person is expected to do

- indicate how one would know if the program is working

During evaluation to:

- document accomplishments

- organize evidence about the program

- identify differences between the ideal program and its real operation

- determine which concepts will (and will not) be measured

- frame questions about attribution (of cause and effect) and contribution (of initiative components to the outcomes)

- specify the nature of questions being asked

- prepare reports and other media

- tell the story of the program or initiative

During advocacy to:

- justify why the program will work

- explain how resource investments will be used

How do you create a logic model?

There is no single way to create a logic model. Think of it as something to be used, its form and content governed by the users' needs.

Who creates the model? This depends on your situation. The same people who will use the model - planners, program managers, trainers, evaluators, advocates and other stakeholders - can help create it. For practical reasons, though, you will probably start with a core group, and then take the working draft to others for continued refinement.

Remember that your logic model is a living document, one that tells the story of your efforts in the community. As your strategy changes, so should the model. On the other hand, while developing the model you might see new pathways that are worth exploring in real life.

Two main development strategies are usually combined when constructing a logic model.

- Moving forward from the activities (also known as forward logic). This approach explores the rationale for activities that are proposed or currently under way. It is driven by But why? questions or If-then thinking: But why should we focus on briefing Senate staffers? But why do we need them to better understand the issues affecting kids? But why would they create policies and programs to support mentoring? But why would new policies make a difference?... and so on. That same line of reasoning could also be uncovered using if-then statements: If we focus on briefing legislators, then they will better understand the issues affecting kids. If legislators understand, then they will enact new policies...

- Moving backward from the effects (also known as reverse logic). This approach begins with the end in mind. It starts with a clearly identified value, a change that you and your colleagues would definitely like to see occur, and asks a series of "But how?" questions: But how do we overcome fear and stigma? But how can we ensure our services are culturally competent? But how can we admit that we don't already know what we're doing?

At first, you may not agree with the answers that certain stakeholders give for these questions. Their logic may not seem convincing or even logical. But therein lies the power of logic modeling. By making each stakeholder's thinking visible on paper, you can decide as a group whether the logic driving your initiative seems reasonable. You can talk about it, clarify misinterpretations, ask for other opinions, check the assumptions, compare them with research findings, and in the end develop a solid system of program logic. This product then becomes a powerful tool for planning, implementation, orientation, evaluation, and advocacy, as described above.

By now you have probably guessed that there is not a rigid step-by-step process for developing a logic model. Like the rest of community work, logic modeling is an ongoing process. Nevertheless, there are a few tasks you should be sure to accomplish.

To illustrate these in action, we'll use another example for an initiative called "HOME: Home Ownership Mobilization Effort." HOME aims to increase home ownership in order to give neighborhood control to the people who live there, rather than to outside landlords with no stake in the community. It does this through a combination of educating community residents, organizing the neighborhood, and building relationships with partners such as businesses.

Steps for drafting a logic model

- Find the logic in existing written materials to produce your first draft.

- Available written materials often contain more than enough information to get started. Collect narrative descriptions, justifications, grant applications, or overview documents that explain the basic idea behind the intervention effort. If your venture involves a coalition of several organizations, be sure to get descriptions from each agency's point of view. For the HOME campaign, we collected documents from planners who proposed the idea, as well as mortgage companies, homeowner associations, and other neighborhood organizations.

- Your job as a logic modeler is to decode these documents. Keep a piece of paper by your side and sketch out the logical links as you find them. (This work can be done in a group to save time and engage more people if you prefer.)

- Read each document with an eye for the logical structure of the program. Sometimes that logic will be clearly spelled out (e.g., The information, counseling, and support services we provide to community residents will help them improve their credit rating, qualify for home loans, purchase homes in the community; over time, this program will change the proportion of owner-occupied housing in the neighborhood).

- Other times the logic will be buried in vague language, with big leaps from actions to downstream effects (e.g., Ours is a comprehensive community-based program that will transform neighborhoods, making them controlled by people who live there and not outsiders with no stake in the community).

- As you read each document, ask yourself the But why? and But how? questions. See if the writing provides an answer. Pay close attention to parts of speech. Verbs such as teach, inform, support, or refer are often connected to descriptions of program activities. Adjectives like reduced, improved, higher, or better are often used when describing expected effects.

- Determine the appropriate scope of the model for its intended users and uses. Consider creating a family of models for multiple users.

- The HOME initiative, for instance, created different models to address the unique needs of their financial partners, program managers, and community educators. Mortgage companies, grant makers, and other decision makers who decided whether to allocate resources for the effort found the global view from space most helpful for setting context. Program managers wanted the closer, yet still broad view from the mountaintop. And community educators benefited most from the you are here version. The important thing to remember is that these are not three different programs, but different ways of understanding how the same program works.

- Check whether the model makes sense and is complete.

- Logic models convey the story of community change. Working with the stakeholders, it's your responsibility to ensure that the story you've told in your draft makes sense (i.e., is logical) and is complete (has no loose ends). As you iteratively refine the model, ask yourself and others if it captures the full story.

- Here are the plot points common in most community change initiatives, presented with their "storytelling" names.

- The Promised Land (desired effects). Does the model show specific measurable results that you hope to achieve? Does it contain big leaps of faith or does it show change through a logical sequence of effects? Are crucial behavioral changes identified (e.g., more applications for home ownership, increased home buying, greater engagement in community and civic affairs, etc.)? And if those behavior changes are supposed to be sustained, does the model explain how community conditions will change to reinforce new behaviors (e.g., home owner support groups, tax cuts on owner-occupied housing, discounts at the local hardware store for customers who own property in the neighborhood, etc.)? In the HOME model, we specified the following sequence of effects:

- Short-term - Potential home owners attain greater understanding of how credit ratings are calculated and more accurate information about the steps to improve a credit rating; mortgage companies create new policies and procedures allowing renters to buy their own homes; local businesses start incentive programs; and anti-discrimination lawsuits are filed against illegal lending practices.

- Mid-term - The community's average credit rating improves; applications rise for home loans along with the approval rate; support services are established for first-time home buyers; neighborhood organizing gets stronger, and alliances expand to include businesses, health agencies, and elected officials.

- Longer-term - The proportion of owner-occupied housing rises; economic revitalization takes off as businesses invest in the community; residents work together to create walking trails, crime patrols, and fire safety screenings; rates of obesity, crime, and injury fall dramatically.

- An advantage of the graphic model is that it can display both the sequence and the interactions of effects. For example, in the HOME model, credit counseling leads to better understanding of credit ratings, while loan assistance leads to more loan submissions, but the two together (plus other activities such as more new buyer programs) are needed for increased home ownership.

- The Promised Land (desired effects). Does the model show specific measurable results that you hope to achieve? Does it contain big leaps of faith or does it show change through a logical sequence of effects? Are crucial behavioral changes identified (e.g., more applications for home ownership, increased home buying, greater engagement in community and civic affairs, etc.)? And if those behavior changes are supposed to be sustained, does the model explain how community conditions will change to reinforce new behaviors (e.g., home owner support groups, tax cuts on owner-occupied housing, discounts at the local hardware store for customers who own property in the neighborhood, etc.)? In the HOME model, we specified the following sequence of effects:

- Drama (activities, interventions). How will obstacles be overcome? Who is doing what? What kinds of conflict and cooperation are evident? What's being done to re-arrange the forces of change? What new services or conditions are being introduced? Your activities, based on a clear analysis of risk and protective factors, are the answers to these kinds of questions, Your interventions reveal the drama in your story of directed social change.

Dramatic actions in the HOME initiative include offering educational sessions and forming business alliances, homeowner support groups, and a neighborhood organizing council. At evaluation time, each of these actions is closely connected to output indicators that document whether the program is on track and how fast it is moving. These outputs could be the number of educational sessions held, their average attendance, the size of the business alliance, etc. (These outputs are not depicted in the global model, but that could be done if valuable for users.)

- Raw Materials (inputs, resources, or infrastructure). The energy to create change can't come from nothing. Real resources must come into the system. Those resources may be financial, but they may also include people, space, information, technology, equipment, and other assets. The HOME campaign runs because of the input from volunteer educators, support from schools and faith institutions in the neighborhood, discounts provided by lenders and local businesses, revenue from neighborhood revitalization, and increasing social capital among community residents.

- Setting (background, context and conditions). Really good stories convey facts, but they also have texture. There is a backdrop against which the main action takes place. Community change always takes place in the context of history, geography, politics, etc. Although it is impossible to represent all of those factors in a model, you can strive to include features that remind users those conditions exist and will affect how change unfolds.

- Stakeholders working on the HOME campaign understood that they were challenging a history of racial discrimination and economic injustice. They saw gentrification occurring in nearby neighborhoods. They were aware of backlash from outside property owners who benefit from the status quo. None of these facts are included in the model per se, but a shaded box labeled History and Context was added to serve as a visual reminder that these things are in the background.

- Attend to the nuts and bolts of drawing the model.

- Draft the logic model using both sides of your brain and all the talents of your stakeholders. Use your artistic and your analytic abilities.

- Arrange activities and intended effects in the expected time sequence. And don't forget to include important feedback loops - after all, most actions provoke a reaction.

- Link components by drawing arrows or using other visual methods that communicate the order of activities and effects. (Remember - the model does not have to be linear or read from left to right, top to bottom. A circle may better express a repeating cycle.)

- Allow yourself plenty of space to develop the model. Freely revise the picture to show the relationships better or to add components.

- Neatness counts, so avoid overlapping lines and unnecessary clutter.

- Color code regions of the model to help convey the main storyline.

- Try to keep everything on one page. When the model get too crowded, either adjust its scope or build nested models.

- Make sure it passes the "laugh test." That is, be sure that the image you create isn't so complex that it provokes an immediate laugh from stakeholders. Of course, different stakeholders will have different laugh thresholds.

- Use PowerPoint or other computer software to animate the model, building it step-by-step so that when you present it to people in an audience, they can follow the logic behind every connection.

- Revisit and be ready to revise the model as necessary.

- Don't let your model become a tedious exercise that you did just to satisfy someone else. Don't let it sit in a drawer. Once you've gone through the effort of creating a model, the rewards are in its use. Revisit it often and be prepared to make changes. All programs evolve and change through time, if only to keep up with changing conditions in the community. Like a roadmap, a good model will help you to recognize new or reinterpret old territory.

- Also, when things are changing rapidly, it's easy for collaborators to lose sight of their common goals. Having a well-developed logic model can keep stakeholders focused on achieving outcomes while remaining open to finding the best means for accomplishing the work. If you need to take a detour or make a longer stop, the model serves as a framework for incorporating the change.

- As you improve, modify or realign your model, take stock of emerging activities and effects. You might need to do one or more of the following:

- Clarify the path of activities to effects and outcomes

- Elaborate links

- Expand activities to reach your goals

- Establish or revise mile markers

- Redefine the boundary of your initiative or program

- Reframe goals or desired outcomes

What makes a logic model effective?

You will know a model's effectiveness mainly by its usefulness to intended users. A good logic model usually:

- Logically links activities and effects

- Is visually engaging (simple, parsimonious) yet contains the appropriate degree of detail for the purpose (not too simple or too confusing)

- Provokes thought, triggers questions

- Includes forces known to influence the desired outcomes

The more complete your model, the better your chances of reaching "the promised land" of the story. In order to tell a complete story or present a complete picture in your model, make sure to consider all forces of change (root causes, trends, and system dynamics). Does your model reveal assumptions and hypotheses about the root causes and feedback loops that contribute to problems and their solutions?

In the HOME model, for instance, low home ownership persists when there is a vicious cycle of discrimination, bad credit, and hopelessness preventing neighborhood-wide organizing and social change. Three pathways of change were proposed to break that cycle: education; business reform; and neighborhood organizing. Building a model on one pathway to address only one force would limit the program's effectiveness.

You can discover forces of change in your situation using multiple assessment strategies, including forward logic and reverse logic as described above. When exploring forces of change, be sure to search for personal factors (knowledge, belief, skills) as well as environmental factors (barriers, opportunities, support, incentives) that keep the situation the same as well as ones that push for it to change.

Take time to simulate

After you've mapped out the structure of a program strategy, there is still another crucial step to take before taking action: some kind of simulation. As logical as the story you are telling seems to you, as a plan for intervention it runs the risk of failure if you haven't explored how things might turn out in the real world of feedback and resistance.

Simulation is one of the most practical ways to find out if a seemingly sensible plan will actually play out as you hope. Simulation is not the same as testing a model with stakeholders to see if it makes logical sense. The point of a simulation is to see how things will change - how the system will behave - through time and under different conditions.

Though simulation is a powerful tool, it can be conducted in ways ranging from the simple to the sophisticated.

- Simulation can be as straightforward as an unstructured role-playing game, in which you talk the model through to its logical conclusions.

- In a more structured simulation, you could develop a tabletop exercise in which you proceed step by step through a given scenario with pre-defined roles and responsibilities for the participants.

- Ultimately, you could create a computer-based mathematical simulation by using any number of available software tools.

The key point to remember is that creating logical models and simulating how those models will behave involve two different sets of skills, both of which are essential for discovering which change strategies will be effective in your community.

What are the benefits and limitations of logic modeling?

You can probably envision a variety of ways in which you might use the logic model you've developed or that logic modeling would benefit your work.

Here are a few advantages that experienced modelers have discovered.

- Logic models integrate planning, implementation, and evaluation. As a detailed description of your initiative, from resources to results, the logic model is equally important for planning, implementing, and evaluating the project. If you are a planner, the modeling process challenges you to think more like an evaluator. If your purpose is evaluation, the modeling prompts discussion of planning. And for those who implement, the modeling answers practical questions about how the work will be organized and managed.

- Logic models prevent mismatches between activities and effects. Planners often summarize an effort by listing its vision, mission, objectives, strategies and action plans. Even with this information, it can be hard to tell how all the pieces fit together. By connecting activities and effects, a logic model helps avoid proposing activities with no intended effect, or anticipating effects with no supporting activities. The ability to spot such mismatches easily is perhaps the main reason why so many logic models use a flow chart format.

- Logic models leverage the power of partnerships. As the W.K. Kellogg Foundation notes (see Internet Resources below), refining a logic model is an iterative or repeating process that allows participants to "make changes based on consensus-building and a logical process rather than on personalities, politics, or ideology. The clarity of thinking that occurs from the process of building the model becomes an important part of the overall success of the program." With a well-specified logic model, it is possible to note where the baton should be passed from one person or agency to another. This enhances collaboration and guards against things falling through the cracks.

- Logic models enhance accountability by keeping stakeholders focused on outcomes. As Connie Schmitz and Beverly Parsons point out (see Internet Resources), a list of action steps usually function as a manager's guide for running a project, showing what staff or others need to do to--for example, "Hire an outreach worker for a TB clinic." With a logic model, however, it is also possible to illustrate the effects of those tasks--for example, "Hiring an outreach worker will result in a greater proportion of clients coming into the clinic for treatment." This short-term effect then connects to mid- and longer-term effects, such as "Satisfied clients refer others to the clinic" and "Improved screening and treatment coverage results in fewer deaths due to TB."

In a coalition or collaborative partnership, the logic model makes it clear which effects each partner creates and how all those effects converge to a common goal. The family or nesting approach works well in a collaborative partnership because a model can be developed for each objective along a sequence of effects, thereby showing layers of contributions and points of intersection.

- Logic models help planners to set priorities for allocating resources. A comprehensive model will reveal where physical, financial, human, and other resources are needed. When planners are discussing options and setting priorities, a logic model can help them make resource-related decisions in light of how the program's activities and outcomes will be affected.

- Logic models reveal data needs and provide a framework for interpreting results. It is possible to design a documentation system that includes only beginning and end measurements. This is a risky strategy with a good chance of yielding disappointing results. An alternative approach calls for tracking changes at each step along the planned sequence of effects. With a logic model, program planners can identify intermediate effects and define measurable indicators for them.

- Logic models enhance learning by integrating research findings and practice wisdom. Most initiatives are founded on assumptions about the behaviors and conditions that need to change, and how they are subject to intervention. Frequently, there are different degrees of certainty about those assumptions. For example, some of the links in a logic model may have been tested and proved to be sound through previous research. Other linkages, by contrast, may never have been researched, indeed may never have been tried or thought of before. The explicit form of a logic model means that you can combine evidence-based practices from prior research with innovative ideas that veteran practitioners believe will make a difference. If you are armed with a logic model, it won't be easy for critics to claim that your work is not evidence-based.

- Logic models define a shared language and shared vision for community change. The terms used in a model help to standardize the way people think and how they speak about community change. It gets everyone rowing in the same direction, and enhances communication with external audiences, such as the media or potential funders. Even stakeholders who are skeptical or antagonistic toward your work can be drawn into the discussion and development of a logic model. Once you've got them talking about the logical connections between activities and effects, they're no longer criticizing from the sidelines. They'll be engaged in problem-solving and they'll be doing so in an open forum, where everyone can see their resistance to change or lack of logic if that's the case.

Limitations

Any tool this powerful must not be approached lightly. When you undertake the task of developing a logic model, be aware of the following challenges and limitations.

First, no matter how logical your model seems, there is always a danger that it will not be correct. The world sometimes works in surprising, counter-intuitive ways, which means we may not comprehend the logic of change until after the fact. With this in mind, modelers will appreciate the fact that the real effects of intervention actions could differ from the intended effects. Certain actions might even make problems worse, so it's important to keep one eye on the plan and another focused on the real-life experiences of community members.

If nothing else, a logic model ought to be logical. Therein lies its strength and its weakness. Those who are trying to follow your logic will magnify any inconsistency or inaccuracy. This places a high burden on modelers to pay attention to detail and refine their own thinking to great degree. Of course, no model can be perfect. You'll have to decide on the basis of stakeholders' uses what level of precision is required.

Establishing the appropriate boundaries of a logic model can be a difficult challenge. In most cases, there is a tension between focusing on a specific program and situating that effort within its broader context. Many models seem to suggest that the only forces of change come from within the program in question, as if there is only one child in the sandbox.

At the other extreme, it would be ridiculous and unproductive to map all the simultaneous forces of change that affect health and community development. A modeler's challenge is to include enough depth so the organizational context is clear, without losing sight of the reasons for developing a logic model in the first place.

On a purely practical level, logic modeling can also be time consuming, requiring much energy in the beginning and continued attention throughout the life of an initiative. The process can demand a high degree of specificity; it risks oversimplifying complex relationships and relies on the skills of graphic artists to convey complex thought processes.

Indeed, logic models can be very difficult to create, but the process of creating them, as well as the product, will yield many benefits over the course of an initiative.

In Summary

A logic model is a story or picture of how an effort or initiative is supposed to work. The process of developing the model brings together stakeholders to articulate the goals of the program and the values that support it, and to identify strategies and desired outcomes of the initiative.

As a means to communicate a program visually, within your coalition or work group and to external audiences, a logic model provides a common language and reference point for everyone involved in the initiative.

A logic model is useful for planning, implementing and evaluating an initiative. It helps stakeholders agree on short-term as well as long-term objectives during the planning process, outline activities and actors, and establish clear criteria for evaluation during the effort. When the initiative ends, it provides a framework for assessing overall effectiveness of the initiative, as well as the activities, resources, and external factors that played a role in the outcome.

To develop a model, you will probably use both forward and reverse logic. Working backwards, you begin with the desired outcomes and then identify the strategies and resources that will accomplish them. Combining this with forward logic, you will choose certain steps to produce the desired effects.

You will probably revise the model periodically, and that is precisely one advantage to using a logic model. Because it relates program activities to their effect, it helps keep stakeholders focused on achieving outcomes, while it remains flexible and open to finding the best means to enact a unique story of change.

Online Resources

The Community Builder’s Approach to Theory of Change: A Practical Guide to Theory Development, from The Aspen Institute’s Roundtable on Community Change.

"Everything You Wanted to Know About Logic Models But Were Afraid to Ask" by Connie C. Schmitz and Beverly A. Parsons.

The CDC Evaluation Working Group provides a linked section on logic models in its resources for project evaluation.

The Evaluation Guidebook for Projects Funded by S.T.O.P. Formula Grants under the Violence Against Women Act includes a chapter on developing and using a logic model (Chapter 2), and additional examples of model in the "Introduction to the Resource Chapters."

A logic model from Harvard that uses a family/school partnership program.

The CDC Evaluation Working Group provides a linked section on logic models in its resources for project evaluation.

Excerpts from United Way's publication on Measuring Program Outcomes See especially "Program Outcome Model."

Logic Model Magic Tutorial from the CDC - this tutorial will provide you with information and resources to assist you as you plan and develop a logic model to describe your program and help guide program evaluation. You will have opportunities to interact with the material, and you can proceed at your own pace, reviewing where you need to or skipping to sections of your choice.

Tara Gregory on Using Storytelling to Help Organizations Develop Logic Models discusses techniques to facilitate creative discussion while still attending to the elements in a traditional logic model. These processes encourage participation by multiple staff, administrators and stakeholders and can use the organization’s vision or impact statement as the “happily ever after.”

Theory of Change: A Practical Tool for Action, Results and Learning, prepared by Organizational Research Services.

Theories of Change and Logic Models: Telling Them Apart is a helpful PowerPoint presentation saved as a PDF. It’s from the Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change.

University of Wisconsin’s Program Development and Evaluation provides a comprehensive template for a logic model and elaborates on creating and developing logic models.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control Evaluation Group provides links to a variety of logic model resources.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation Logic Model Development Guide is a comprehensive source for background information, examples and templates.

Print Resources

American Cancer Society (1998). Stating outcomes for American Cancer Society programs: a handbook for volunteers and staff. Atlanta, GA, American Cancer Society.

Julian, D. (1997). The utilization of the logic model as a system level planning and evaluation device. Evaluation and Program Planning 20(3): 251-257.

McEwan, K., & Bigelow, A. (1997). Using a logic model to focus health services on population health goals. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 12(1): 167-174.

McLaughlin, J., & Jordan, B. (1999). Logic models: a tool for telling your program's performance story. Evaluation and Program Planning 22(1): 65-72.

Moyer, A., Verhovsek, et al. (1997). Facilitating the shift to population-based public health programs: innovation through the use of framework and logic model tools. Canadian Journal of Public Health 88(2): 95-98.

Rush, B. & Ogbourne, A. (1991). Program logic models: expanding their role and structure for program planning and evaluation. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 6: 95-106.

Taylor-Powell, E., Rossing, B., et al. (1998). Evaluating collaboratives: reaching the potential. Madison, WI, University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension.

United Way of America (1996). Measuring program outcomes: a practical approach. Alexandria, VA, United Way of America.

Western Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies. (1999) Building a Successful Prevention Program. Reno, NV, Western Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies.

Wong-Reiger, D., & David, L. (1995). Using program logic models to plan and evaluate education and prevention programs. In Love, A. Ed. Evaluation Methods Sourcebook II. Ottawa, Ontario, Canadian Evaluation Society.